Dev life

Mission to Mars – PyCon 2014

We had a blast at PyCon 2013 with our giant email-powered Nerf gun. It was a big crowd-pleaser and for PyCon 2014, we wanted to do something even cooler. So of course, it was obvious that we should start with… a vacuum cleaner. This blog shows you how we went from vacuum cleaner to Mars Rover and ended up having a great time again this year at PyCon.

PUBLISHED ON

We had a blast at PyCon 2013 with our giant email-powered Nerf gun. It was a big crowd-pleaser and for PyCon 2014, we wanted to do something even cooler. So of course, it was obvious that we should start with… a vacuum cleaner. This blog shows you how we went from vacuum cleaner to Mars Rover and ended up having a great time again this year at PyCon.

Table of contents

From humble beginnings…a mission to Mars

Anton, our resident electrical engineer turned software developer had bought himself a Neato robotic vacuum after doing extensive research, comparing Neato against the more popular iRobot Roomba. The deciding factor? Neato vacs have an API which allows you to control the vac through code. Just what we’d need for our mission to Mars.

One of the many things we like about working at Rackspace, the company that acquired Mailgun in 2012, is the monthly hackday where all the engineers in the office get together to work on anything they find interesting, whether it is related to an official Rackspace project, or not. We pulled in a couple of our Rackspace buddies and spent the day working on the code that we’d use to control the robot.

We knew that we wanted to give people the ability to email commands to the robot as a control mechanism and that the robot should be able to move forward, backward and spin 360 degrees. We also wanted to be able to “take samples” from the Martian surface, ok, that means turn on the vacuum, and take a picture using the camera mounted to what would become the rover’s main instrument tower.

How it works

Many of the details for our PyCon game this year were different, but there was one thing that we learned from last year:

Network access could be tricky at the conference venue. The Rasberry Pi IP address may not be publicly accessible so submitting an HTTP POST to it may not be possible.

To solve this, we used Redis to make sure the rover could retrieve commands from the server as long as Raspberry Pi has an Internet connection. Here is what that looks like conceptually:

+ - - - - - +

+-----------+ +------------+

+--------------+ | | | | | |

| | SMTP | | HTTP | |

| Email client +-----> | Mailgun +-----> | Web server | |

| | | route | | |

+--------------+ | | | | | |

| | +-----+------+

+-----------+ | | |

Redis lpush

| (local) |

|

| v |

+--------------+ +------------+

| | Redis brpop | | | |

| Raspberry Pi | <----------------+ Redis |

| robot brain | (Internet) | | | |

| | +------------+

+------+-------+ + - - - - - +

|

|

|

| Camera interface +-------------------+

+-------------------> | Raspery Pi Camera |

| GPIO +-------------------+

+-------------------> | Brick Pi |

| serial port +-------------------+

+-------------------> | Neato Vac |

+-------------------+

With the solved, we worked on the core controls.

Below are samples of the code that we used to actually control the Robot:

Control the camera tower with BrickPi:

def init(host, password):

"""Init the required components."""

print "Init BrickPi"

BrickPiSetup()

BrickPi.MotorEnable[PORT_D] = 1

def camera_control(command, mission_control_address):

print "Camera control module received:", command

if command in ("up", "down"):

if command "up":

BrickPi.MotorSpeed[PORT_D] = -100

elif command "down":

# despite the fact that the surface gravity of Mars is only

# about 38% of Earth's there is still less force required to

# bring the camera down

BrickPi.MotorSpeed[PORT_D] = 50

BrickPiUpdateValues()

sleep(0.5)

# stop the motor

BrickPi.MotorSpeed[PORT_D] = 0

BrickPiUpdateValues()

elif command == "take_picture":

camera.capture(file_name)

send_picture(file_name, mission_control_address)

def send_picture(file_name, mission_control_address)

"""Send picture back to the Mission Control Center."""

r = requests.post(

"https://api.mailgun.net/v2/mailgun.net/messages",

auth=("api", "***"),

files=[("attachment", open(file_name))],

data={"from": "Mars Rover <mars@mailgun.net>",

"to": mission_control_address,

"cc": "nsa@mailgun.net", # oops

"subject": "A message from Mars",

"text": "The picture of the surface is attached!"})

Control the vacuum:

def init(host, password):

print "Init Vacuum Base!!!"

vac_port = serial.Serial("/dev/ttyACM1")

def vac_run_command(command, read_response=True):

print "Vacuum base control module received:", command

try:

vac_port.write(command)

if not read_response:

# provided command doesn't have a response

return

return read_response()

except:

# fault tolerance for the WIN!

reconnect()

Accepting POST requests from Mailgun:

@app.route('/mission_control', methods=['POST'])

def mission_control():

"""Commands from Mailgun arrive here."""

command_message = request.form['stripped-text']

from_ = request.form['From']

for command in parse(command_message):

robot.run(command, from_)

return "10-4"

We’re going to need more Legos

With the software done, we set about turning our vacuum cleaner into a Mars Rover.

We started by searching around for the best place to buy single-color Legos in bulk. We needed a lot of black, grey and white Legos if we were going to create an authentic Rover. Turns out that Ebay is the best place to get legos, often by the pound. $118 later, we were ready to get started.

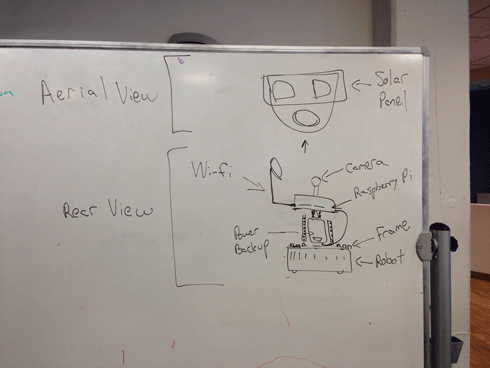

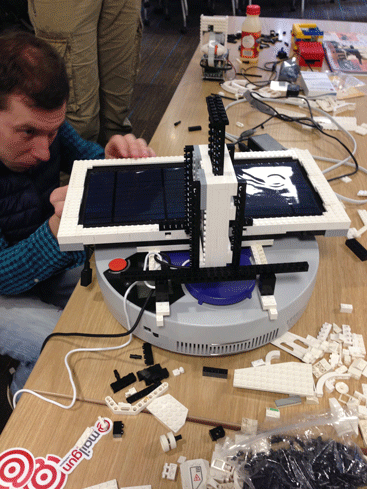

We assembled a crack team of engineers for the mission, including the 4-year-old son of one of the Mailgunners, and laid out all the Legos that would form the rover body. Here you see Anton, Ralph, and Luca setting up. After prototyping a few of the major components, we formalized our design. The rover would have an oscillating camera (powered by a Mindstorm Lego motor) mounted on top of a control tower with integrated Raspberry Pi, BrickPi and battery backup. A large part of the rover body would also be covered by a working USB solar panel.

A few missteps, a few laughs, and a few hours later, we were well on our way to having an assembled robot to demo at the hackday presentation that was coincidentally scheduled for later that day at the Rackspace office.

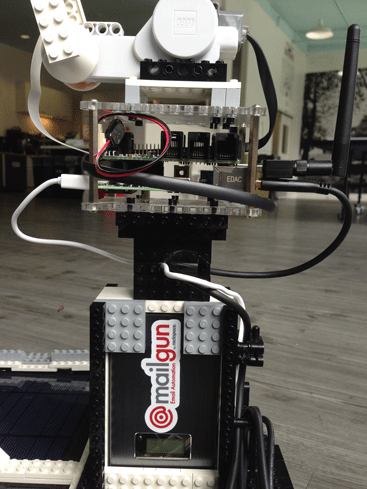

And here’s a close up of the main control tower. The thing with the Mailgun sticker is the battery backup. The Raspberry Pi and BrickPi are mounted on top of that and you can see the Lego motor at the top of the photo. The Raspberry Pi camera is just out of the frame.

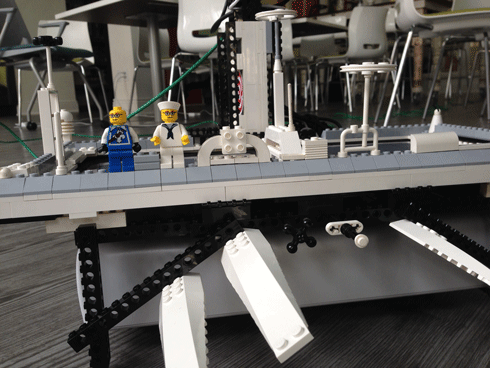

Here’s a rear view of the Rover. Much of the decorative chrome was added by our youngest mission member, including the 2 lego people. One of them is a sailor, and one is a pirate. This turned out to be just one part of the mission that would require some major creativity as you will see later.

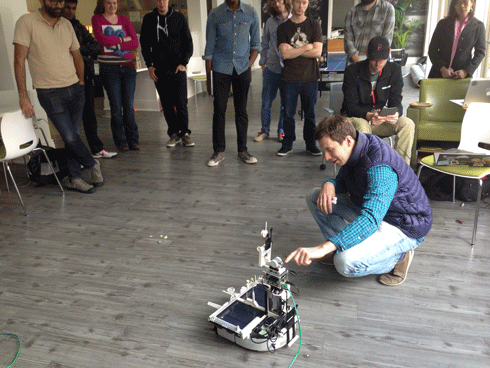

We finished a long day by demoing the Rover to our office. Here is Anton going over the finished Rover.

Dear TSA,

We knew we couldn’t bring the Rover on the plane to Montreal with us. It looks like a bomb, we admit that, and we didn’t want to have a nice long conversation with a team of TSA agents. So we carefully packed the Rover into a large suitcase, protected it with about 30 nice, soft American Apparel 50-50 t-shirts that we’d hand out to people at the conference who took the Rover for a spin. We also included a note to the TSA letting them know that this was a robot made using a Raspberry Pi. We were sure that they’d open the bag and take a look, but we didn’t bank on how closely they’d look.

New and improved…but not by choice

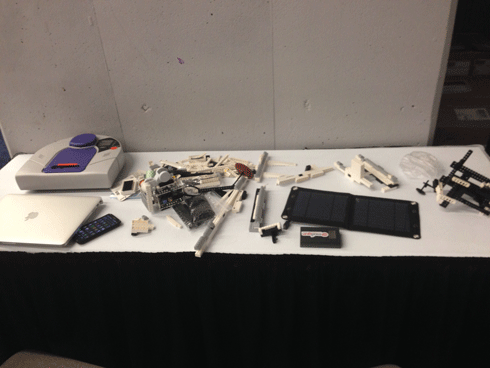

When we arrived at our hotel in Montreal and opened the suitcase, our first thought was, dang, they must have really thrown the bag around, cause a lot of the pieces have come completely apart. On closer inspection though, it became clear that the TSA had disassembled the Rover, practically Lego by Lego. Some components were still intact, but the most complex structures, like the frame and the control tower, had been meticulously taken apart.

Coffee in hand, and 2 hours before the conference opening, we set the Legos out on a table, again, and started reassembling. The problem we ran into was that we hadn’t brought any extra Legos. Because we had winged the initial design, we didn’t have a blueprint to follow and so each Lego would have to be placed exactly how it was before if we were to keep the original design.

Needless to say, we ended going with a slightly different design, one that ended up using about 30% fewer Legos to create the same functional design.

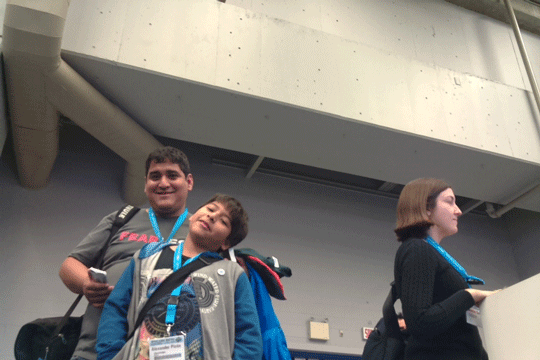

While frustrating at first, the reconstruction of the Rover turned out to be a blast. We ended up talking to a ton of Lego enthusiasts during the morning and some even jumped in and helped a bit. By mid-day, our Mars Rover was fully operational and a great way to meet the Python community. Some of our favorite hackers that we met were the young ones coming to PyCon for the first time. Here’s a shot taken from the Rover’s own camera after our young friend controlled the bot by emailing in commands from his Dad’s phone. We’d say the mission was a success!

So that’s the story of our Mars Rover. No matter what, we always have a blast at PyCon. We can’t wait till next year when we do it all over again.

Till then! Happy Sending.

The Mailgunners.